The team at Cider is Wine are on a mission to change our perception of cider and curry not being a good match and have put together this piece for Curry Culture on the subject.

“Of course there’s no such thing as ‘curry’”

This will come as a shock to the many Brits who patronise the 12,000 or so ‘curry restaurants’ that contributed some £5 billion to the UK economy in 2019, and to all those who continue to buy ready-prepared curry dishes in the hundreds of thousands from our supermarkets.

For those interested in how this misnomer came about, curry is actually an anglicised form of the Tamil word kaṟi meaning ‘sauce’ or ‘relish for rice’ that uses the leaves of the curry tree: it probably entered the language via the British East India Company in the mid-1600s as a spice blend called kari podi… curry powder is another anglicisation – and this is not an authentic Indian spice either!

So what’s it all about?

In India whether a dish has sauce or not it’s referred to by its specific name like Sindhi Murgh, Dum Aloo, Jeera Aloo, Matar Paneer. Calling these dishes curries would be like calling all noodle dishes ‘spaghetti’ or all Japanese dishes ‘sushi’.

The Indian food we find in Britain has come a long way since those ‘curry houses’ started proliferating in the 1950s and ‘60s serving their ubiquitous curry sauces (mild, not really that hot, and burning) and we now find Indian restaurants more and more as beacons of fine cuisine, even gaining Michelin stars: looking at the UK as a whole, just think Atul Kochhar’s Sindhu in Marlow and Kanishka in London, Vivek Singh’s Cinnamon Club, also in London, Aktar Islam and Jabbar Khan’s Lasan in Birmingham, Anand George’s Purple Poppadom in Cardiff and Monir Mohammed’s Mother India in Glasgow.

What best to drink to complement your Indian meal?

If all you’re after is a fiery experience, then it probably doesn’t matter that much – all you want is a cooling liquid that ideally is not too gassy (Cobra beer was created – in England – for exactly that reason). However, if you want something that marries with the aromatics of the best Indian cuisine, then you’re actually better off with cider – but not any old cider.

Cider suffers from some of the image problems that can still bedevil Indian food in the sense of just how authentic it really is. Lax regulations mean that most mass market ciders consist of just 35% juice, all of which can be from concentrate (from pretty well anywhere). The point of these ciders, like lagers, is that they are homogeneous and their lack of lack character is really not an issue.

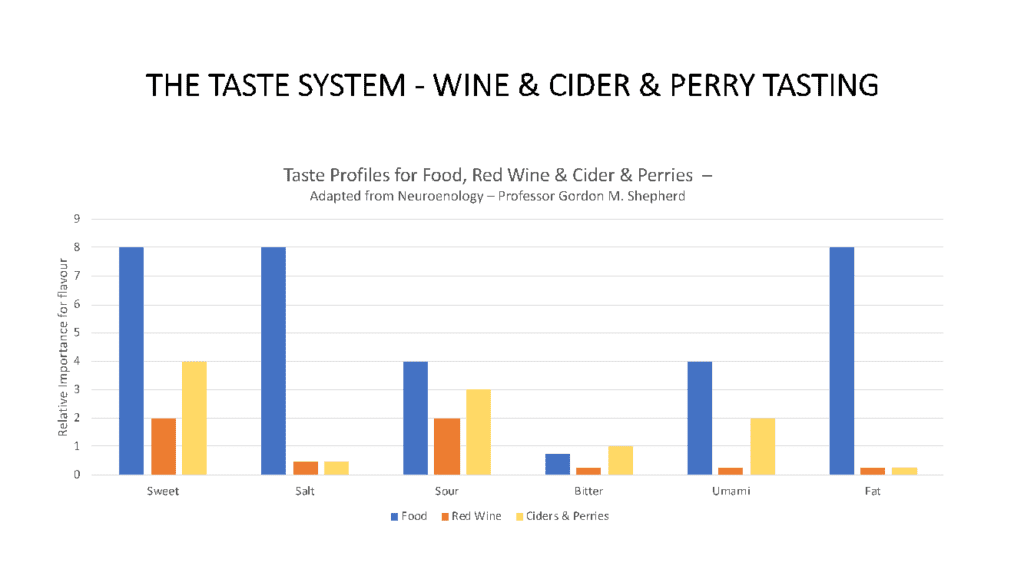

Wines can struggle with the aromatics of Eastern and South Asian cuisines, whereas those ciders and perries made exclusively from 100% apples (or pears) without using any concentrates provide the drinker with a range of full flavour profiles that can be a perfect match with the dishes being served. The chart below demonstrates the taste profiles of wine, ciders and different foods. Foods tend to spike with different flavour characteristics and the reasons that ‘fast food’ is not healthy is because it contains high levels of a combination of the three areas, sweet, salt and fat. Ciders feature umami, sourness and sweetness, which give them more balancing aspects on the palate than wine, thus being able to match the aromatics, spice and sweet and sour of Indian food more proficiently than wines.

100% fruit content not-from-concentrate ciders – ciders made like wines (in dictionary terms a wine can be made from any fruit and EU regulations stipulate that wine made from grapes must be made from 100% fruit without any concentrates) are the opposite of homogeneous and 100% characterful.

As a wine writer recently commented “The difference that this makes is amazing”.

These ciders are redolent of the locality where they are grown (what winemakers call ‘terroir’), the apple or pear varieties used – there are thought to be as many as 60,000 apple varieties, but ‘only’ 10,000 grape varieties – and the skills of the individual cidermaker working to bring out the most appealing characteristics of the fruit.

Taking English ciders as an example, full juice ciders using apple varieties grown in the west of England are perhaps bolder and earthier and closer in taste profile to a red wine, whilst the apples used by cidermakers in the east and south east are lighter and brisker, and closer to a white wine. This is only the ‘tip of the iceberg’, as it were, and talking about ‘ice’, then there are some stunning examples of so-called ice ciders where the juice is frozen, which concentrate the juice, to create a cider that balances wonderful sweetness with refreshing acidity – and these ciders are a great accompaniment to the likes of Gajar Ka Halwa or Mysore Pak, to give just a couple of examples (let’s eat more Indian desserts, please!).

This has led to chefs reappraising ciders, recognising that they can be used to complement all the hard work that can go into creating a dish and greatly heighten the dining pleasure and so are now finding a rightful place on finer dining menus.

In addition to this ciders and perries fermented exclusively from apples and pears are by their nature gluten free, almost all vegan (every cider on cideriswine.co.uk/shop bar one is vegan) and around half the alcohol of the equivalent size of a bottle of wine.

From sparkling to still, from light golden to amber (pink too) and from the driest of the dry to the sweetest of the sweet, and every point in-between, what’s sure is that there’s a cider to suit every palate – and every Indian ‘curry’.

It’s surely time to re-evaluate both curry and cider.

Six Great Cider and Perry Matches to Six Curry Culture Dishes

Share this Story